Most of us entering the mining industry today will still be here 30 years from now.

Many tailings facilities built today will require monitoring for more than 100 years.

That gap is not accidental. It is a design decision.

Tailings management is not merely a storage problem. It is a century-scale risk management challenge. The decisions made during feasibility and early-stage design directly influence long-term geotechnical stability, geochemical evolution, water treatment requirements, and closure liability.

Acid mine drainage (AMD), long-term seepage, and perpetual water treatment are not random failures. They are the cumulative outcomes of system-level choices made at the beginning of a project.

Research by Blowes et al. (1991) demonstrated the central role of sulphide oxidation in generating acid mine drainage under unsaturated conditions. The interaction between oxygen diffusion, moisture content, and reactive sulphide minerals governs long-term geochemical behavior — often decades after closure.

Similarly, the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM, 2020) emphasizes lifecycle thinking, from site selection to post-closure monitoring, reinforcing that tailings facilities must be designed for long-term consequence management, not just operational containment.

The Structural Gap: Mine Life vs Facility Life

A mine may operate for 10–25 years.

A tailings storage facility (TSF) may require active monitoring for multiple generations.

This mismatch creates structural risk.

When throughput, recovery, and capital efficiency dominate early decision-making, long-term geotechnical and geochemical exposure can become secondary. Yet post-closure risk does not disappear; it transitions into environmental and financial liability.

As emphasized by the International Commission on Large Dams (ICOLD, 2011), tailings dams require design frameworks that account for long-term stability and consequence classification well beyond operational life.

Reducing Risk at the Source

If tailings represent future liability, risk reduction must begin upstream.

1. Waste Reduction Through Smarter Ore Targeting

Selective mining and optimized ore processing can reduce tailings volume. While high-grading alone is not universally viable, minimizing unnecessary waste directly reduces long-term storage requirements.

2. Strategic Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB)

Cemented paste backfill returns processed tailings underground, reducing surface storage volumes and contributing to ground support.

However, backfill capacity is limited by operational constraints, binder cost, curing time, and stope availability. Studies on CPB mechanical performance (e.g., Koohestani et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2018) show that strength gain, fracture behavior, and post-peak performance significantly influence underground stability.

Backfill reduces footprint — but it does not eliminate surface storage.

3. Filtered and Dry-Stack Tailings

Filtered tailings reduce water content and improve shear strength, lowering hydraulic risk. However, unsaturated conditions can still promote sulphide oxidation and long-term geochemical evolution (Blowes et al., 1991).

Dry-stack improves physical stability — but does not inherently eliminate chemical risk.

4. Hybrid Systems

The most realistic pathway forward may be hybrid integration:

- Backfill

- Filtered or thickened tailings

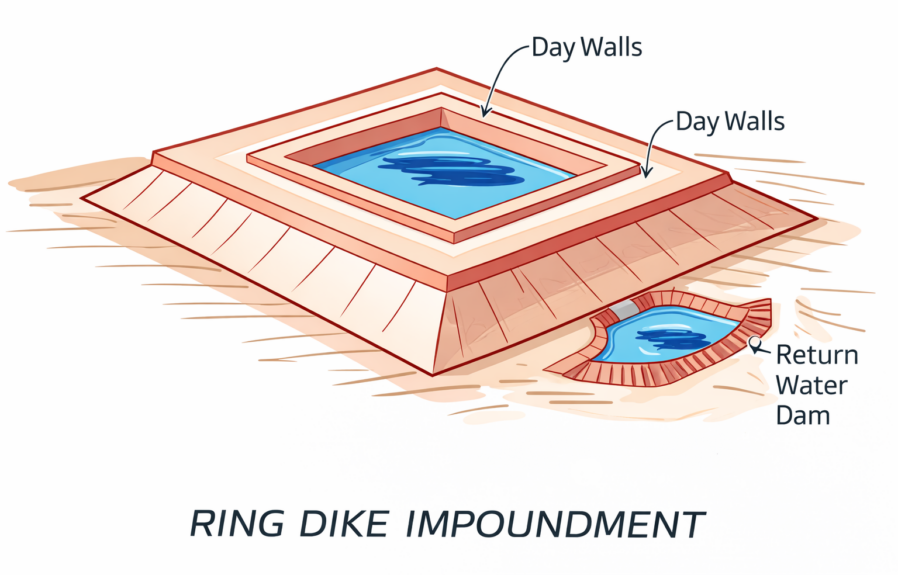

- Engineered TSFs

- Geochemical risk mitigation

Surface storage is unlikely to disappear. But its risk profile can be intentionally reduced.

Backfill: Beyond Compressive Strength

Backfill design is often evaluated using 7-, 28-, or 90-day unconfined compressive strength (UCS) targets.

But underground performance depends on more than peak strength.

Fracture behavior under loading, pore structure evolution, and sulphide oxidation under unsaturated conditions influence long-term geomechanical and geochemical stability.

Fredlund & Rahardjo (1993) emphasized the importance of unsaturated soil mechanics in understanding suction, permeability, and oxygen diffusion — mechanisms directly relevant to backfill and tailings systems exposed to fluctuating saturation conditions.

Backfill is not simply a structural material. It becomes part of the rock mass system.

Design decisions today influence stress redistribution, cracking behavior, and oxidation pathways decades into the future.

That is lifecycle engineering.

The Responsibility of This Generation

The industry increasingly requires engineers who can:

- Integrate geotechnical and geochemical thinking

- Understand sulphide oxidation mechanisms

- Evaluate long-term closure exposure

- Balance operational constraints with lifecycle risk

The future of tailings management will not be defined by larger facilities.

It will be defined by how intentionally we reduce long-term exposure from the outset.

The real question is not whether tailings will remain part of mining.

The question is whether we design them as temporary production infrastructure — or as century-scale environmental systems.

References

Blowes, D. W., Ptacek, C. J., Jambor, J. L., & Weisener, C. G. (1991). The geochemistry of acid mine drainage.

Fredlund, D. G., & Rahardjo, H. (1993). Soil Mechanics for Unsaturated Soils.

Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (2020).

ICOLD (2011). Tailings Dams – Risk of Dangerous Occurrences.

Koohestani, B., et al. (2016). Mechanical behavior of cemented paste backfill.

Sun, Q., et al. (2018). Fracture and strength characteristics of CPB.