The selection of a tailings management system is never generic. It is fundamentally site-specific, shaped by geology, topography, climate, seismicity, environmental sensitivity, and social context. In practice, the “best” option is not the most conventional one, but the alternative that best balances technical feasibility, risk, environmental stewardship, and community impact.

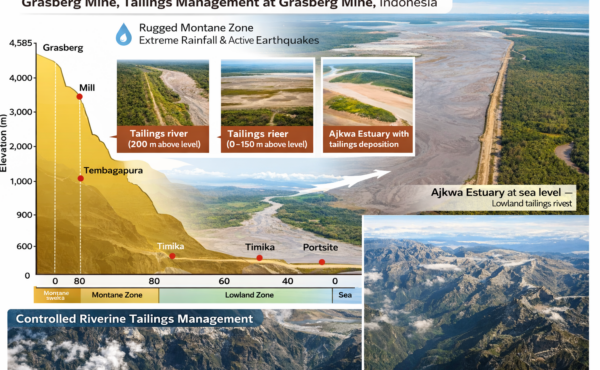

A compelling illustration of this decision-making process comes from Grasberg Mine in Indonesia, one of the world’s largest copper and gold operations.

Site Context

Grasberg is located at approximately 4,000 meters above ground level, in extremely rugged mountainous terrain characterized by steep slopes, high rainfall, and active seismic conditions. Over its operational life — projected to extend to 2041 — the mine was expected to generate about 3 billion tonnes of tailings. This massive volume of waste placed significant constraints on viable management options.

Given these conditions, three primary tailings disposal strategies were evaluated.

Option 1: Conventional Containment Dams

The most common global approach to tailings storage — building large containment dams — proved highly problematic at Grasberg.

Constructing valley dams in the mountainous terrain was impractical because the slopes were too steep to support sufficient storage. Even with two extremely large dams, one 250 meters high and another 300 meters high (approaching world-record scale for earth-fill dams), the system would have retained only 0.9 billion tonnes of tailings — less than one-third of what was required.

A lowland ring dam was also considered. This would have required approximately 100 square kilometers of land enclosed by a 20-meter-high embankment. However, placing such a massive tailings facility in a region with intense rainfall and frequent earthquakes posed unacceptable risks. Large tailings dams in wet, seismically active environments are statistically more prone to failure than those in arid, geologically stable regions.

As a result, conventional dam-based storage was ruled out as a safe or practical solution.

Option 2: Sub-Aqueous Pipeline Disposal

The second option involved transporting tailings through a network of long-distance slurry pipelines to a remote deposition site.

This concept required constructing multiple parallel pipelines ranging from 180 to over 300 kilometers in length, capable of carrying up to 300,000 tonnes of tailings per day. While technically possible, this approach introduced serious operational and environmental vulnerabilities.

Slurry pipelines are highly sensitive to flow velocity. If the flow is too fast, it accelerates pipe erosion and wear; if too slow, solids can settle and cause blockages. To accommodate fluctuating production rates, pipe diameters would have needed to vary between 26 and 40 inches, adding complexity and maintenance challenges.

Additionally, the proposed pipeline route traversed areas prone to landslides, heavy rainfall, and seismic activity, making it difficult to protect against ruptures or failures. Ultimately, the route was deemed technically and logistically untenable.

Option 3: Controlled Riverine Tailings Management (Selected Option)

With both conventional dams and long-distance pipelines deemed impractical, the mine adopted Controlled Riverine Tailings Management (CRTM).

Instead of attempting to confine tailings within artificial structures, this approach used an existing river channel to transport tailings from the mountainous mine site to a managed deposition area in the lowlands. Crucially, this system incorporated multiple engineering and environmental controls to mitigate risks.

Key components included:

- Bio-filter retention programs, where grasses and trees were planted to enhance sediment capture, stabilize deposits, reduce erosion, and improve soil conditions.

- Fill Back Swamp Program, using excavators to create channels that guided tailings into lower-elevation zones within the Tailings Deposition Area (TDA).

- Levee construction and maintenance, using heavy equipment to build containment structures that kept tailings within designated zones.

- Reno mattresses, placed along levees to prevent scouring during flood events.

- Ongoing sedimentation modeling and topographic surveys to track changes in deposition patterns over time.

- Tailings utilization, where suitable materials were repurposed for infrastructure development.

- Quality assurance testing, including MASW and CPT investigations to characterize the geotechnical properties of deposited sediments and levees.

- Comprehensive environmental monitoring, covering water quality, hydrology, geomorphology, meteorology, sediment chemistry, air quality, biodiversity, and toxicological impacts on aquatic life.

Why CRTM Was Chosen

Despite being controversial, the controlled riverine system was judged to be the preferred option because:

- Sediment impacts could be actively managed and adjusted over time.

- The risk of catastrophic structural failure was lower than with mega-dams.

- In the event of localized failures, the broader system would not collapse in the same way a large dam might.

From an engineering standpoint, CRTM represented the least hazardous alternative under the extreme site conditions at Grasberg.

A Broader Lesson

Grasberg highlights a difficult reality in mining and environmental engineering: technical compliance does not guarantee social or environmental acceptability.

Even though riverine disposal operated within regulatory frameworks at the time, the ecological and social consequences — including impacts on downstream ecosystems and communities — sparked intense criticism and debate.

The case underscores that tailings management is not solely an engineering problem. It is also a question of ethics, governance, risk tolerance, and responsibility to affected environments and populations.