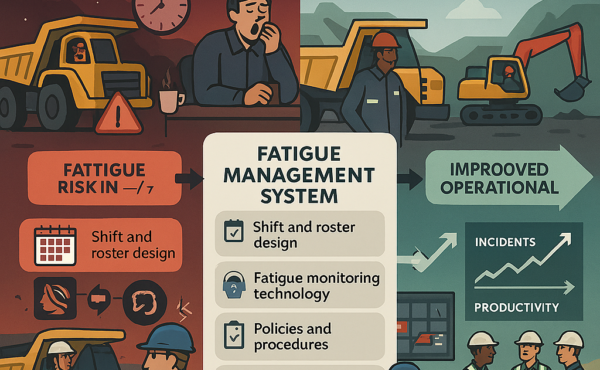

In 24/7 mining operations, fatigue is more than a byproduct of hard work; it is a critical safety hazard. Research indicates that being awake for 17 to 19 hours can impair a worker’s performance as much as a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05%, doubling the risk of operational errors. For an industry that relies on heavy machinery and high-vigilance tasks, effectively implementing a Fatigue Risk Management System (FRMS) is essential for both safety and productivity.

Effective implementation moves beyond simple “compliance” with hours-of-service regulations. It requires a “defense-in-depth” approach—a multi-layered strategy that integrates technology, culture, and scientific modeling to catch fatigue before it leads to an incident.

Shift design and predictive modeling

The foundation of fatigue management begins before a worker even sets foot on the mine site. Traditional rostering often ignores the biological reality of the circadian rhythm.

Effective systems utilize biomathematical models to analyze rosters. Tools like Readi or FAST (Fatigue Avoidance Scheduling Tool) use algorithms to predict “fatigue hotspots” based on sleep opportunities and shift rotations. Key scheduling best practices include:

- Forward-rotating shifts: moving from day to afternoon to night shifts is easier for the body to adjust to than backward rotations.

- Limiting night shifts: capping consecutive night shifts helps prevent the “sleep debt” that accumulates when workers struggle to sleep during daylight hours.

- Commute accounting: operations must factor in travel time, especially for Fly-In Fly-Out (FIFO) workers, as long commutes can consume vital rest periods.

Layered monitoring technology

A robust FRMS uses both predictive and reactive technologies. While scheduling models predict potential risk, real-time monitoring catches active impairment.

- Wearable biometrics: devices such as smart bands (e.g., SmartCap) monitor brain activity or heart rate variability to provide a real-time “score” of a worker’s alertness.

- In-cab sensors: camera-based systems like Caterpillar’s DSS monitor eye-closure (microsleeps) and head position. While these are reactive—meaning fatigue is already present—they serve as a final safety net to prevent collisions.

- Psychomotor vigilance tests (PVT): short, tablet-based reaction tests at the start of a shift can help supervisors identify workers who are starting their day already impaired by poor sleep.

Cultivating a “fatigue-resistant” culture

Technology is only as effective as the culture supporting it. In many mining environments, there is a “tough it out” mentality that discourages workers from admitting they are tired. Effective implementation requires:

- Non-punitive self-reporting: workers must feel safe reporting fatigue without fear of losing pay or facing disciplinary action.

- Supervisory training: supervisors need to be trained to recognize the “soft signs” of fatigue, irritability, slowed speech, or loss of situational awareness, and have the authority to reassign tasks or mandate “power naps.”

- Shared responsibility: the “Swiss Cheese Model” of risk management posits that safety is a shared burden. The company provides the schedule and tools, but the worker is responsible for utilizing their rest periods for actual sleep.

Continuous improvement through data

An FRMS is not a “set and forget” program. Implementation must include a feedback loop where data from incidents and near-misses is analysed against fatigue levels. If a particular haul road consistently sees “lane departure” alerts at 3:00 AM, the system must be agile enough to adjust lighting, task rotation, or break schedules for that specific area.

Conclusion

Effectively managing fatigue in 24/7 mining requires moving from a culture of “working hours” to a culture of “risk management.” By combining predictive scheduling, real-time monitoring, and a supportive workplace culture, mining operations can significantly reduce the 35–60% of incidents typically linked to human fatigue.