Geological uncertainties are identified as a major risk factor in high-stake environments such as mineral extraction. Unlike other types of risks that can be managed using various tools such as hedging or management strategies, geological uncertainties are inherent due to a lack of knowledge about a certain area. Quantification of such uncertainties is important for progressing beyond base case estimates.

Quantifying geological uncertainty

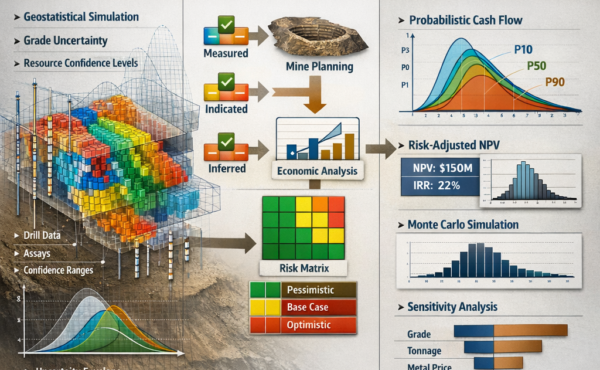

The quantification of geological uncertainty has evolved from deterministic “best-guess” estimates to sophisticated probabilistic frameworks. Contemporary methods rely heavily on geostatistical simulation and stochastic modeling to represent the spatial variability of mineral grades and orebody geometry.

Geostatistical and stochastic methods

Geostatistical techniques, such as kriging, remain a cornerstone of resource estimation because they incorporate spatial relationships and provide explicit uncertainty estimates at unsampled locations (Menandro et al., 2025). However, kriging often results in “smoothed” models that may underrepresent extreme values. To address this, researchers increasingly employ conditional simulation, which generates multiple equiprobable realizations of the orebody. Each realization reflects the statistical and spatial characteristics of the primary data while honoring the measured values at drill-hole locations.

Recent advancements have also integrated Machine Learning (ML) to enhance these models. Algorithms such as Random Forest and Artificial Neural Networks are utilized to process large datasets and identify complex, non-linear patterns that traditional statistics might miss (Wulder et al., 2022). These ML approaches are often used in tandem with Sensitivity Analysis to evaluate how specific input parameters, such as density, dispersivity, or structural continuity, propagate through the model to influence final results (Nahodilová et al., 2022).

Incorporating uncertainty into financial models

Once quantified, these geological realizations must be translated into financial terms. The integration process typically follows a stochastic transfer function, where each geological model is passed through a mine plan and a cost model to produce a range of possible economic outcomes.

Probabilistic financial frameworks

Instead of a single Net Present Value (NPV), modern financial models utilize Monte Carlo Simulations or Stochastic Mine Planning. By running thousands of simulations, financial analysts can derive a probability distribution of the NPV, providing a clearer picture of the project’s risk profile.

- Safety analysis: models now include preliminary site safety and stability assessments based on descriptive geological models, which are then integrated into the broader long-term safety and economic analysis (Valter et al., 2023).

- Risk-averse decision making: decision-scaling and Robust Decision Analysis frameworks allow companies to adapt their mine plans in response to different levels of uncertainty and risk averseness, ensuring that the selected plan remains viable under various geological scenarios (Hoang, 2024).

Strategic value and real options

The incorporation of uncertainty also enables the use of Real Options Valuation (ROV). This method treats the mining project as a series of options—such as the option to expand, contract, or defer development—based on the resolution of geological uncertainty over time. This approach acknowledges that management can make informed decisions as new data (e.g., from infill drilling) becomes available, reducing the initial risk premium of the project.

Conclusion

Quantifying geological uncertainty requires a shift from static models to dynamic, probabilistic systems. By leveraging geostatistical simulations, machine learning, and robust decision-making frameworks, mining companies can create financial models that do not just ignore uncertainty but embrace it as a manageable variable. This integration ensures that capital is allocated more efficiently and that projects are designed to withstand the inherent unpredictability of the natural world.

References

Hoang, L. N. (2024). Adaptation planning under climate change uncertainty using multi-criteria robust decision analysis in a water resource system. White Rose eTheses Online. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/5567/

Menandro, J., Cardoso Bastos, R., & Mastrantonis, S. (2025). Selecting the best habitat mapping technique: A comparative assessment for fisheries management in Exmouth Gulf. Frontiers in Marine Science, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2025.1570277

Nahodilová, R., Valter, M., & SÚRAO. (2022). Methodology for selecting the final and backup sites for the Czech deep geological repository. SÚRAO. https://surao.gov.cz/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/TZ759_2024_ENG-2.pdf

Valter, M., Nahodilová, R., & SÚRAO. (2023). SÚRAO Research & Development Plan 2024-2028. SÚRAO Publications. https://surao.gov.cz/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/TZ746_2024_ENG-1.pdf

Wulder, M. A., Hermosilla, T., & White, J. C. (2022). Machine learning for complex pattern extraction in large datasets. Remote Sensing of Environment, 270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2022.112857