In the contemporary global discourse, economic success is often attributed to political stability, democratic institutions, and sound fiscal policy. While these factors are undeniably influential, a growing body of scientific literature suggests that the fundamental “deeper determinants” of a nation’s trajectory are rooted in its physical and chemical composition—its geology. As the world pivots toward a green energy transition and high-tech industrialization, the distribution of lithological resources is increasingly dictating which nations thrive, often transcending the immediate impacts of political shifts (McCord & Sachs, 2013).

The geological blueprint of development

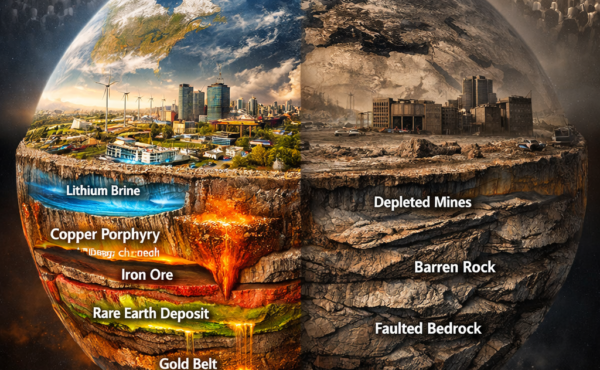

The initial divergence in global wealth can be traced back to biophysical and geophysical characteristics. Research indicates that while market institutions were critical to historical milestones like the Industrial Revolution, they were insufficient without accessible geological reserves, such as massive coal deposits (McCord & Sachs, 2013). This “geography school” of thought posits that the physical environment, including distance to coasts, soil composition, and mineral depth, shapes the long-term potential for capital accumulation and productivity.

In the modern era, this reliance has shifted from coal to a new class of materials. The “green energy transition” is not merely a policy choice but a massive geological undertaking. National prosperity in the 2020s and beyond is increasingly tied to the possession of Critical Raw Materials (CRMs), such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements (REEs) (Akcil et al., 2024).

Critical minerals: the new geopolitical currency

The demand for minerals like zirconium and platinum is projected to grow significantly through 2026, driven by the expansion of nuclear power and electronic supply chains (Zaccaria et al., 2021). Nations that possess these specific geological signatures find themselves at the center of the global economy. For example, Australia’s economic outlook is now heavily contingent on its role as a primary exporter of lithium and nickel, which are essential for battery cell performance and longevity (Stinson & Cam, 2025).

Unlike fossil fuels, these minerals are highly concentrated geographically. For instance, rare earth deposits are largely confined to a few specific regions, and the ability of a country to tap into these deep subsurface or extreme environments, such as the deep sea or polar regions, will likely determine its strategic importance (Bae & Lee, 2026). Politics may manage the trade of these resources, but it cannot create them where the geology does not permit.

Beyond the “resource curse”

Historically, the “natural resource curse” suggested that abundant mineral wealth often led to slow growth and political instability. However, recent scientific perspectives argue that the rising “metal intensity” of the global economy is changing this dynamic. Modern extractive industries now generate significant spillovers into other sectors, with every dollar invested in mining contributing nearly double that in total turnover for the national economy.

Furthermore, the “Carbon Neutrality 2.0” era is forcing a structural transformation in research and development. Governments are now prioritizing “geoscience governance,” investing in AI-driven platforms and integrated earth system modeling to maximize the efficiency of their geological assets (Bae & Lee, 2026). In this context, the scientific ability to map and exploit the subsurface becomes a more reliable predictor of success than the prevailing political ideology of the day.

Conclusion

As global demand for critical minerals surges through 2026, the traditional view of politics as the primary driver of national wealth is being challenged by the reality of geological scarcity. While governance remains important for internal stability, the external “destiny” of a nation is being rewritten by its lithological endowments. In the race for technological supremacy and climate resilience, geology provides the deck of cards; politics merely decides how to play them.

References

Akcil, A., Swami, K. R., Gardas, R. L., Hazrati, E., & Dembele, S. (2024). Overview on Hydrometallurgical Recovery of Rare-Earth Metals from Red Mud. Minerals, 14(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/min14060587

Bae, S., & Lee, J.-W. (2026). Future technology strategies for the geoscience sector: Insights from STEEP and SWOT analyses. Frontiers in Earth Science, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2025.1743903

McCord, G. C., & Sachs, J. D. (2013). Development, Structure, and Transformation: Some Evidence on Comparative Economic Growth (Working Paper No. 19512). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w19512

Stinson, H., & Cam, I. (2025). The Global Energy Transition and Critical Minerals | Bulletin – October 2025. (October). https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2025/oct/the-global-energy-transition-and-critical-minerals.html

Zaccaria, D., Vicentini, N., Perna, M. G., Rosatelli, G., Sharygin, V. V., Humphreys-Williams, E., Brownscombe, W., & Stoppa, F. (2021). Lamprophyre as the Source of Zircon in the Veneto Region, Italy. Minerals, 11(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/min11101081