In modern blasting, the transition from traditional non-electric systems (such as shock tubes or detonating cords) to electronic detonators marks a significant technological leap. While non-electric systems remain the “workhorse” of the industry due to their simplicity and lower unit cost, electronic systems offer a level of precision and safety that is reshaping mining, quarrying, and civil construction. Let’s explore the advantages and limitations of electronic detonators compared to NONEL.

Precision and timing accuracy

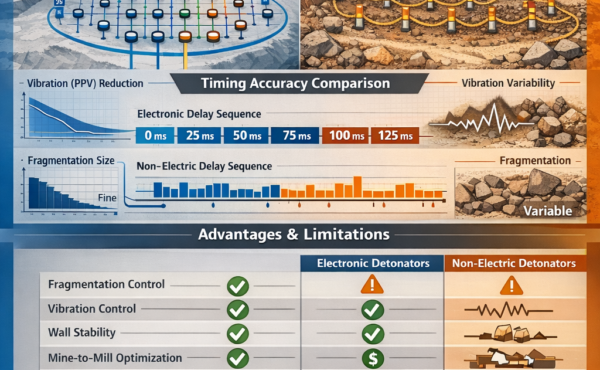

The most fundamental difference lies in how delays are achieved. Non-electric detonators rely on a pyrotechnic delay element, a chemical powder train that burns at a specific rate [1]. Because of inherent variances in chemical composition and manufacturing, these have a “scatter” or error margin of roughly 3% to 5%.

In contrast, electronic detonators use a microchip and a ceramic clock to control timing. This allows for:

- Near-zero scatter: accuracy is typically within ± 0.1 ms, compared to tens or hundreds of milliseconds in pyrotechnic systems [2].

- Programmability: engineers can program delays in 1 ms increments on-site, allowing for customized firing sequences that are impossible with “fixed-delay” non-electric tubes [3].

- Optimized fragmentation: Precise timing ensures that each borehole “relieves” the burden for the next, resulting in more uniform rock sizes. Studies have shown a 20-25% reduction in mean block size when switching to electronic systems [4].

Safety and security advantages

Safety protocols have been fundamentally enhanced by digital integration.

- Immunity to extraneous energy: electronic detonators are designed to be “inherently safe” against stray currents, static electricity, and radio frequency interference. They cannot be fired by a standard battery or even a lightning strike in the same way traditional electric or some non-electric systems might be vulnerable.

- Two-way communication: before a blast is initiated, the blasting machine “talks” to every detonator. It can identify a broken wire or a faulty unit in the circuit, allowing technicians to fix issues before the shot is fired. This has reduced misfire rates from roughly 1% in non-electric systems to below 0.1%.

- Security: electronic systems require a specific “key” or digital code to fire. This makes stolen detonators virtually useless to unauthorized individuals.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their technical superiority, electronic detonators face hurdles that prevent them from completely replacing non-electric systems.

Higher unit cost

The primary deterrent is the price. An electronic detonator can cost five to ten times more than a non-electric shock tube. While this cost is often offset by “downstream” savings, such as reduced fuel consumption in crushers due to better rock fragmentation, the initial capital expenditure remains a barrier for smaller operations.

Complexity and training

Non-electric systems are valued for their “plug-and-play” simplicity. Electronic systems require:

- Specialized hardware: loggers and blasters specific to the manufacturer.

- Intensive training: blasters must be tech-literate, capable of using software to design blast patterns and troubleshoot digital error codes.

Environmental fragility

While robust, the delicate micro-circuitry within an electronic detonator can be damaged by extreme dynamic shock from adjacent boreholes if the timing is not perfectly managed. Furthermore, the connectors can be sensitive to heavy moisture or mud, requiring meticulous handling during the “tie-in” process.

Modern blasting is increasingly moving toward a “total cost” model. While electronic detonators are more expensive upfront, their ability to protect nearby infrastructure through vibration control and reduce secondary breaking costs makes them the preferred choice for sophisticated 21st-century projects.

References

[1] pcm_admin, “Benefits of Electronic Delay Detonators,” Quarry. Accessed: Jan. 21, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.quarrymagazine.com/benefits-of-electronic-delay-detonators/

[2] M. Cardu, A. Giraudi, and P. Oreste, “A review of the benefits of electronic detonators,” Rem: Rev. Esc. Minas, vol. 66, pp. 375–382, 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0370-44672013000300016.

[3] B. L. Wedding Joshua Hoffman, William Chad, “Electronic Detonator and Modern Non-Electric Shocktube Detonator Accuracy,” OneMine. Accessed: Jan. 21, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.onemine.org/documents/electronic-detonator-and-modern-non-electric-shocktube-detonator-accuracy

[4] M. Cardu, A. Giraudi, and P. Oreste, “A review of the benefits of electronic detonators,” Rem: Rev. Esc. Minas, vol. 66, pp. 375–382, 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0370-44672013000300016.