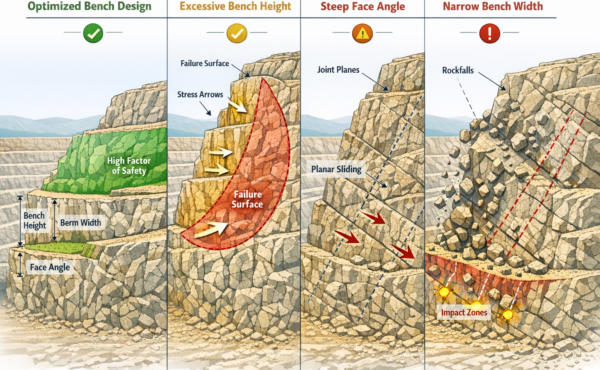

In open-pit mining and civil engineering, the configuration of benches, comprising their height, width, and face angle, is the primary tool for mitigating slope failure. These three parameters do not act in isolation; they create a geometric framework that dictates whether a slope remains stable or becomes susceptible to mechanisms like planar, wedge, or toppling failure.

The role of bench face angle (BFA)

The bench face angle is the inclination of the individual bench wall relative to the horizontal. It is the most critical factor in controlling kinematic failures, particularly in rock masses where discontinuities (joints, bedding planes, or faults) are present.

- Planar failure: this occurs when a single discontinuity “daylights” or intersects the bench face. If the BFA is steeper than the dip of the discontinuity, the block of rock above that plane is unsupported and can slide.

- Wedge failure: when two discontinuities intersect and their line of intersection dips out of the face, a wedge-shaped block can fail. A steeper BFA increases the likelihood of undercutting these intersections, triggering a collapse.

- Toppling: in cases where vertical or near-vertical joints dip into the slope, a very steep BFA can create a lack of horizontal confinement, causing slabs of rock to rotate or “topple” outward.

The impact of bench height

Bench height (H) significantly influences the Factor of Safety (FoS) and the scale of potential failures. While the BFA controls the type of failure, height often controls the magnitude.

- Stress distribution: increasing bench height increases the gravitational load and shear stress at the toe of the bench. Research indicates that as height increases, the FoS typically decreases at a parabolic rate.

- Failure volume: higher benches create larger potential “backbreak” distances. If a failure occurs on a 20-meter bench, the volume of debris is significantly greater than a failure on a 10-meter bench, potentially overwhelming safety systems below.

- Structural interaction: higher benches are more likely to intersect a greater number of persistent joints or geological anomalies, increasing the statistical probability of a kinematic instability.

The function of bench width (Berm Width)

The bench width, often referred to as the catch berm, acts as the last line of defense. Its primary role is not to prevent the initial failure but to arrest and contain it.

- Rockfall containment: ss rocks or debris fall from upper benches, the width must be sufficient to stop them from bouncing or rolling onto the active haul roads or work areas below.3 A common rule of thumb is that the width should be at least 4.5m + 0.2H.

- Spill capacity: when a bench face fails, the material occupies a volume larger than its original state (the “swell factor”). The width must be designed to accommodate this “spill pile” without allowing it to crest over to the next level.

- Inter-ramp stability: collectively, the width of multiple benches determines the inter-ramp angle. Wider benches create a shallower overall slope, which improves global stability by reducing the overall driving force behind deep-seated circular failures.

Ultimately, bench design is a balance between safety and economics. While shallower angles and wider benches are safer, they increase the “stripping ratio” (the amount of waste rock removed to access ore), making the project more expensive. Engineers use limit equilibrium and kinematic analysis to find the “optimum” configuration where these risks are managed within acceptable limits.