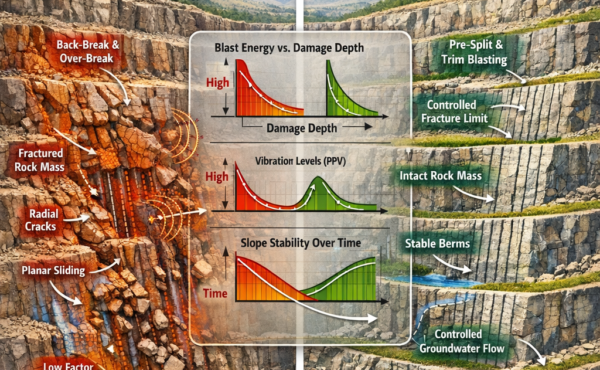

Blasting is a cornerstone of modern rock excavation, yet only about one-third of explosive energy is used for fragmentation; the remainder is dissipated as noise, flyrock, and seismic vibrations (Simangunsong et al., 2024). These vibrations and the resulting Blast-Induced Damage Zone (BIDZ) pose significant threats to the long-term integrity of open-pit benches and highwalls.

Mechanisms of long-term degradation

The impact of blasting on slope stability is not limited to the immediate moment of detonation. It involves a progressive deterioration of the rock mass through several key mechanisms:

- Cumulative micro-fracturing: repeated or cyclic blasting induces cumulative damage. Micro-cracks and pores within the rock mass initiate, propagate, and coalesce under dynamic loading, gradually reducing the overall rock mass strength (Fu et al., 2024).

- Structural activation: high-frequency seismic waves can activate pre-existing geological weaknesses, such as joints or bedding planes, far beyond the intended excavation boundary. These fractures often serve as the paths of least resistance for explosive energy (Etchells et al., 2013).

- Tensile and shear damage: stress waves (R-waves) moving along the slope surface can exceed the rock’s tensile strength, while horizontal shear stress—often the primary trigger for shear failure—destabilizes the slope through abrupt stress redistribution (Sun, 2023; Simangunsong et al., 2024).

- Weathering acceleration: blast-induced fractures increase the surface area of the rock mass exposed to environmental factors. Over time, water infiltration and pore pressure fluctuations within these new cracks accelerate weathering, further lowering the Factor of Safety (FoS) (Carter et al., 2023).

Impact on stability (Factor of Safety)

The long-term impact is quantified through the Factor of Safety (FoS). Research indicates that dynamic loading from production blasting can reduce the FoS by approximately 11% to 13% compared to static conditions (Simangunsong et al., 2024). Furthermore, stability has been found to deteriorate significantly once the Peak Particle Velocity (PPV) exceeds critical thresholds, such as 10.9 mm/s in certain vulnerable mining environments (Simangunsong et al., 2024). A notable “lag effect” has also been observed, where cumulative displacements can increase by over 30% several hours after the blasting event occurred (Simangunsong et al., 2024).

Mitigation strategies

Minimizing blast damage is essential for ensuring the serviceability of a slope over a design life that may span decades or even centuries for mine closure (Carter et al., 2023).

Advanced blast design

Effective damage control begins with optimizing blast parameters. Increasing the burden (the distance between the blast hole and the free face) has a significant negative impact on stability if not properly balanced, as it increases confinement and forces more energy into the remaining rock mass (Simangunsong et al., 2024). Using decoupled charges and adjusting the linear charge factor are critical for limiting damage to final walls (Etchells et al., 2013).

Specialized wall control techniques

To protect the final slope face, engineers employ specialized techniques:

- Presplitting: creating a continuous fracture plane along the final wall before the main production blast to shield the highwall from vibration.

- Trim Blasting: using smaller, more controlled charges near the final wall to limit the depth of the BIDZ (Etchells et al., 2013).

Monitoring and predictive modeling

The use of Peak Particle Velocity (PPV) monitoring allows engineers to set allowable vibration limits based on the specific geomechanical properties of the site. Modern approaches now utilize Bayesian predictive models and radar remote sensing to correlate blasting activity with real-time slope deformation, enabling proactive adjustments to blast designs before failure occurs (Sun et al., 2021; Simangunsong et al., 2024).

References

Carter, T. G., Lorig, L. J., Eberhardt, E., & de Graaf, P. J. H. (2023). Approaches for estimating slope breakback and stability longevity for closure of large open pits. Atlantis Highlights in Engineering, 505–521. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-258-3_49

Etchells, S., Sellers, E., & Furtney, J. (2013). Understanding the blast damage mechanisms in slopes using observations and numerical modelling. Proceedings of the 2013 International Symposium on Slope Stability in Open Pit Mining and Civil Engineering. https://doi.org/10.36487/acg_rep/1308_97_etchells

Fu, B., Ji, H., Pei, J., & Wei, J. (2024). Numerical computation-based analysis of blasting vibration effects and slope stability in an open-pit quarry. Fire, 7(11), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7110420

Simangunsong, G. M., Prassetyo, S. H., & Pinem, R. S. (2024). Relationship between blasting operation and slope stability: A case study at Borneo Indo Bara open pit coal mine. Scientific Reports, 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81784-2

Sun, J., Jia, Y., Zhang, Z., & Yao, Y. (2023). Study on blast-induced ground vibration velocity limits for slope rock masses. Frontiers in Earth Science, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1098630

Sun, P., Lu, W., Hu, H., Zhang, Y., Chen, M., & Yan, P. (2021). A Bayesian approach to predict blast-induced damage of high rock slope using vibration and sonic data. Sensors, 21(7), 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21072473